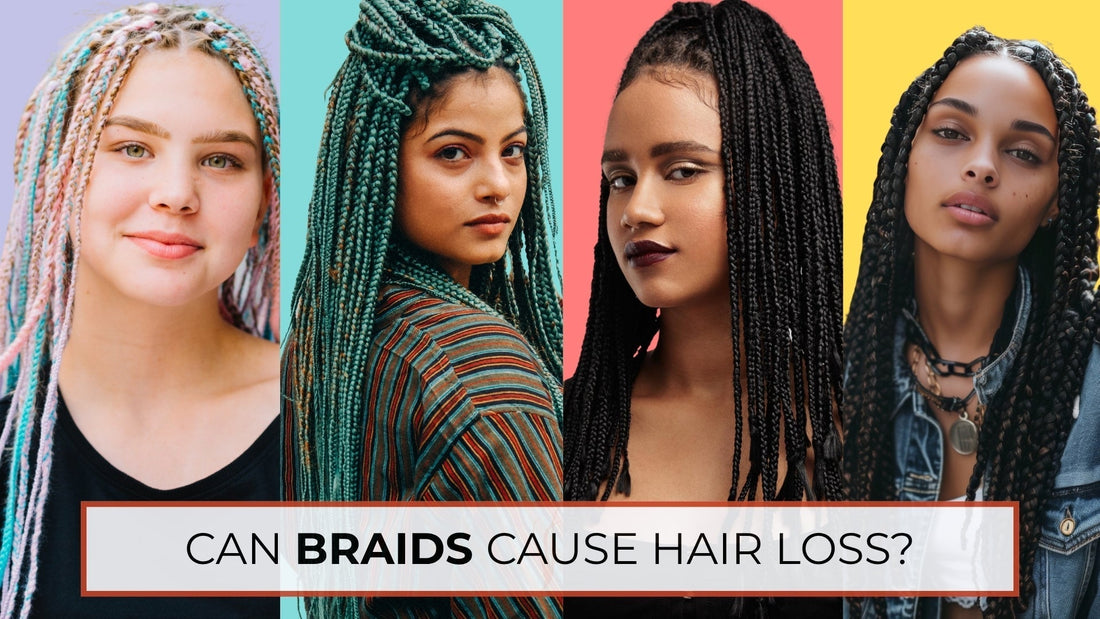

Yes. Braids can cause hair loss when they’re installed too tightly, worn for too long, or made heavy with extensions. The medical name is traction alopecia. It’s preventable in early stages and often reversible if you loosen up and give the scalp recovery time.

What Are Braids?

Braids here include box braids, cornrows, microbraids, French/Dutch braids, twist styles, and braided extensions. Many people call these “protective styles.” They can be protective, yes, when tension and weight are controlled and the scalp gets breaks. The risk comes from how they’re done… not from the existence of braids themselves.

Can Braids Really Cause Hair Loss?

Yes. The condition is traction alopecia, hair loss from repetitive or prolonged tension on follicles. It’s reported across ethnicities but especially in women of African descent, and it often begins young. Early TA is non-scarring and reversible. Long-standing TA can scar and become permanent. That’s the fork in the road.

Epidemiology has measured this. In South African population studies, prevalence reached 17.1% in schoolgirls and 31.7% in women, with disease associated with particular hairstyles and chemical processing. Cultural history matters; so does technique.

What Is Traction Alopecia and How Does It Happen?

Mechanism, in human terms. Tight styling exerts mechanical stress on the hair shaft and follicle. Repeated traction can provoke perifollicular inflammation and eventually fibrosis if the tension continues. Early on, follicles can recover. Later, if scarring sets in, they don’t.

On the scalp this looks like tenderness, bumps, redness, thinning along tension lines and, under trichoscopy, hair casts, broken hairs, black dots. Newer dermoscopic descriptions include the “flambeau sign”—linear white tracks pointing in the direction of pull. Very visual once you’ve seen it.

Yes, it’s preventable. But only if we don’t ignore those early signals.

Which Braided Styles Carry the Highest Risk?

Risk is about tightness, duration, size, and weight. Patterns most often implicated include microbraids, cornrows installed tightly, weaves or braided extensions adding heavy weight, and tight ponytails/buns. Locs that become long and heavy can also strain margins over time. Children and teens are uniquely vulnerable because habits start early and scalps are sensitive.

Practical rule that works: if you feel pain, see bumps or crusting, or get a tension headache after install… it’s too tight. Adjust or remove.

What Are the Early Warning Signs?

- Soreness, stinging, or tenderness along the hairline or braid rows

- Perifollicular erythema and folliculitis (“braid bumps”)

- Broken hairs, widening parts, fine “fringe” hairs persisting at the frontotemporal edge

- Trichoscopy: hair casts, black dots, short broken hairs, and—described recently—the flambeau sign

And that “fringe sign” you might have heard of is a keeper—short hairs at the very edge that survive while behind them density thins. It’s a clinical clue steering the diagnosis toward traction rather than some other alopecia.

Is Braid-Related Hair Loss Permanent?

It can be. If you stop the traction early, regrowth usually appears over months, because follicles remain viable. If traction continues for years, fibrosis can develop, and the loss becomes scarring and permanent. The difference is time and tension.

Some readers ask, realistically… “How long to see baby hairs again?”

It varies by history and inflammation but months is a reasonable window once traction stops and treatment starts.

What Increases the Risk Of Hair Loss From Braids?

- Duration of wear with no breaks

- Small braid size like microbraids

- Added weight from long or heavy extensions

- Chemical relaxers or heat that weaken shafts and compound mechanical stress

- Younger age and cumulative years of styling under tension

- Genetic or coexisting scalp conditions that lower the threshold for damage

An independent lab work shows chemical straighteners can reduce tensile strength and increase brittleness. So, hair tolerates traction less. That doesn’t mean “never style,” it means design styles around biology.

How to Prevent Hair Loss While Enjoying Braids

You don’t have to abandon braids to protect your edges. You just have to rethink them.

- Ask your stylist for looser installation, especially at the hairline. Pain is a stop sign, not a rite of passage.

- Favor larger, looser sections instead of microbraids. Keep extensions lighter and avoid extreme length.

- Rotate styles and schedule scalp breaks.

- Keep the scalp clean and address coexisting inflammation so you’re not stacking stressors.

- For children and teens: no painful styles, avoid heavy beads, and teach them to speak up about discomfort.

Beauty and heritage are not at odds with biology. The sweet spot is a comfortable scalp plus a style you love.

What If I Already Notice Thinning Edges?

First, stop or loosen traction. Many early cases rebound within 3–6 months once tension is removed, especially if inflammation is treated. Seek care sooner than later if there’s pain, redness, crusting, or you’re not seeing progress. A dermatologist or trichologist can confirm the diagnosis, assess scarring vs non-scarring, and set a plan.

And yes, diagnostic tools exist beyond the naked eye. Trichoscopy can visualize those hair casts, broken hairs, and other TA markers; biopsy may be used if the picture is mixed.

Evidence-Based Treatments for Braid-Related Hair Loss

Cornerstone: remove the traction and redesign your styling habits. Everything else is secondary if the pull continues.

Anti-inflammatory Therapy in Early TA

When the scalp shows perifollicular erythema or folliculitis, clinicians commonly use topical corticosteroids and sometimes intralesional triamcinolone in early, non-scarring cases. In a small case series using 5 mg/mL triamcinolone every 6–8 weeks, all subjects showed visible density improvement along the frontotemporal hairline. That’s promising, but note the sample size.

Minoxidil as an Adjunct for Regrowth

Topical minoxidil supports regrowth where follicles remain. Reviews mention improvement in TA within a broader minoxidil evidence base. Clinicians also sometimes use low-dose oral minoxidil off-label; small series and case reports in TA exist, and a 2023 JAAD note reported improved hair density. It’s cautious optimism, not a silver bullet. Discuss benefits and side effects with your doctor.

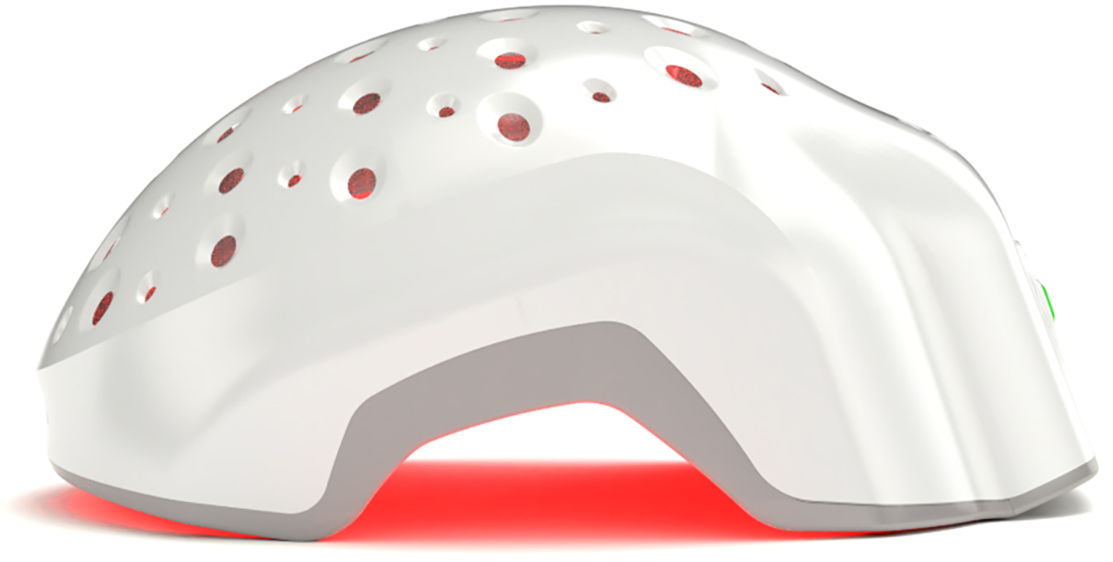

Laser Phototherapy (LPT)

High-quality trials and meta-analyses show LPT improves hair counts in androgenetic alopecia for men and women, and multiple home devices are FDA-cleared for pattern hair loss. For traction alopecia specifically, controlled trials are limited, so we present LPT as a reasonable adjunct in non-scarring phases, with transparent expectation-setting.

PRP and Microneedling

PRP has growing evidence in androgenetic alopecia, but TA-specific data are sparse—mostly small reports or case descriptions, sometimes alongside microneedling. If used, frame it as adjunctive and experimental for TA.

Hair Transplantation

For stable, long-standing scarring TA, surgical restoration can be considered. Outcomes depend on disease stability, degree of scarring, and donor supply; graft survival is generally lower in scarring alopecias than in androgenetic alopecia. Candidacy and timing are everything.

Myths and Misconceptions about Braids and Hair Loss

-

“Braids make hair stronger.” They can reduce daily manipulation, but tight braids create traction and can injure follicles. Balance is key.

-

“If your hair is thick, you’re safe.” Hair texture doesn’t make anyone immune to physics. Tension over time wins.

-

“Supplements will protect my edges.” The fix for traction is mechanical and behavioral, not a pill. (And we keep the conversation rooted in treatments with clinical backing.)

How Do Doctors Diagnose Traction Alopecia?

Diagnosis begins with history and exam, often supported by trichoscopy to document signs like hair casts, broken hairs, and the flambeau pattern. In uncertain cases or when scarring is suspected, a biopsy distinguishes scarring vs non-scarring and guides prognosis.

Differentials that can mimic TA include androgenetic alopecia, central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA), alopecia areata, and tinea capitis. Getting the label right avoids wrong turns.

When Should You See A Dermatologist Or Trichologist?

- You notice persistent thinning along the hairline or rows

- You have redness, bumps, or crusting that doesn’t settle

- You’ve stopped traction for several months without regrowth

- You see shiny, scar-like patches where hair used to be

The earlier the pivot, the friendlier the prognosis. Always.

Conclusion

Braids can be beautiful, cultural, practical. They become risky when pain is normalized and breaks are ignored. Looser installation, smarter weight, and rotation keep the style you love aligned with the scalp you need. If a style hurts… it’s simply not protective.