Hair care in the 1800s relied on infrequent washing, heavy oils and animal fats, aggressive brushing, and early chemical solutions. Most routines focused on appearance and control rather than scalp biology or hair growth, because follicles were not yet understood as living, responsive structures.

Hair Care in the 1800s Was About Control

In the 19th century, hair was treated as a surface material. Something to polish, weigh down, or hold in place. The follicle itself was largely invisible, conceptually and literally. Microscopy was still emerging, and dermatology as a specialty had not yet matured.

So people worked with what they could see. Shine meant health. Smoothness meant strength. If hair stayed put and looked glossy, the routine was considered successful. Growth, shedding, and thinning were framed as fate, age, or moral weakness, not biology.

That framing matters. Because it explains almost everything that followed.

(We’ll come back to this.)

How Often Did People Wash Their Hair in the 1800s?

Short answer… not often.

The Monthly or Seasonal Wash

For many households, full hair washing happened monthly. Sometimes even less. Washing required hauling water, heating it, mixing soap by hand, and scrubbing without modern drains. It was labor. Real labor.

Diaries and domestic manuals from the period describe hair washing as an event, not a habit. Something planned. Something endured.

Why Frequent Washing Was Considered Harmful

There was also fear. Many believed water weakened the scalp, stripped protective oils, or invited illness. Cold water especially was blamed for headaches, nervous disorders, even hair loss.

So instead of washing, people maintained hair through other means. Mostly mechanical ones.

Brushing as Hygiene: The Backbone of Hair Care

Brushing was hygiene.

The 100-Stroke Rule and Oil Redistribution

You’ve probably heard of the “100 strokes a day” rule. Brushing removed dust, soot, and debris from hair while spreading sebum from scalp to ends.

From a mechanical standpoint, this actually helped reduce breakage. Oil lowers friction along the hair shaft. That part checks out.

Growth, though, is a different story.

Brushes, Combs, and Materials Used

Brushes were commonly made with boar bristles. Combs came from bone, horn, wood, sometimes metal. Fine-toothed combs doubled as lice control, which mattered more than we often admit.

Clean scalp meant fewer parasites. That alone shaped routines.

What People Used to Clean Hair When They Did Wash It

When water entered the picture, it wasn’t gentle.

Soap, Lye, and Early Cleansers

Most soaps were alkaline. Very alkaline. Made from animal fat and lye. Effective at removing grease. Brutal on hair fibers.

Hair often felt stiff, rough, and tangled afterward. Which is exactly why oils followed.

Ammonia and Borax Solutions

Diluted ammonia or borax appeared in some recipes as degreasers. They worked. Briefly.

They also left hair dry and brittle, and irritated the scalp. People noticed the damage, but options were limited.

Egg Yolks, Herbal Waters, and Vinegar Rinses

Some turned to gentler alternatives. Beaten egg yolks for slip. Rosemary water for scent. Vinegar rinses to counter soap residue.

These did not nourish follicles. But they helped hair behave better. Subtle difference, but an important one.

Conditioning and Styling Meant Heavy Coating

This is where oils and fats took center stage.

Macassar Oil and Furniture Covers

Macassar oil, often made from coconut or palm oil with fragrance, was wildly popular among men. So popular that it stained upholstery. Hence antimacassars. Decorative cloths meant to protect chairs.

That detail alone tells you how heavy these products were.

Bear Grease, Lard, and Beef Marrow

Bear grease carried symbolic weight. Bears had thick fur. Therefore bear fat must encourage hair.

In reality, much of it was adulterated with pig fat. It added shine and hold. Nothing more. But the belief stuck.

Castor Oil and the Illusion of Thickness

Castor oil was thick. Sticky. Hard to remove. Which made hair clump together visually.

That clumping looked like fullness. Density by illusion. Not by biology.

(Sound familiar?)

Styling Tools and Heat Damage Before Electricity

Heat styling existed long before plugs.

Fire-Heated Tongs and Singed Hair

Curling tongs were heated directly in fire. Temperature control was guesswork. Singed ends were common.

People accepted it as the price of style.

Rag Curls and Lower-Damage Methods

Rag curls were slower. Gentler. Wrapped overnight. No heat required.

Low tech. Less damage. Sometimes the smarter choice.

Hair Growth Claims, Tonics, and Early Marketing

This is where things got loud.

Alcohol-Based Tonics and “Stimulation”

Many tonics were alcohol heavy. Some added botanical extracts. Others included irritants like cantharides.

The scalp tingled. Users felt something happening. That sensation sold the story.

Testimonials

Advertising leaned on testimonials. Not controlled studies. Regulation was minimal. Claims were bold.

Hair loss desperation filled the gap where evidence should have been.

What Physicians Actually Said

Medical journals from the late 1800s grew increasingly skeptical. Some physicians warned against irritants. Others admitted no treatment reliably reversed baldness.

Honesty was slower than marketing. But it arrived.

Dangerous Beauty: When Hair Care Crossed Into Harm

Not everything was harmless.

- Lead-based combs were marketed to darken gray hair

- Arsenic appeared in depilatories and cosmetic treatments

- Mercury showed up in skin and scalp salves

- Lye caused burns when misused

- Flammable solvents were used in early dry cleansers

Safety standards came much later.

What the 1800s Got Right, Accidentally

Some practices helped. Not for the reasons people thought.

Mechanical oil distribution reduced breakage.

Low washing frequency avoided constant fiber swelling.

Protective styles limited friction.

None of this addressed follicles. But hair shafts survived better.

What Modern Trichology Says About These Practices

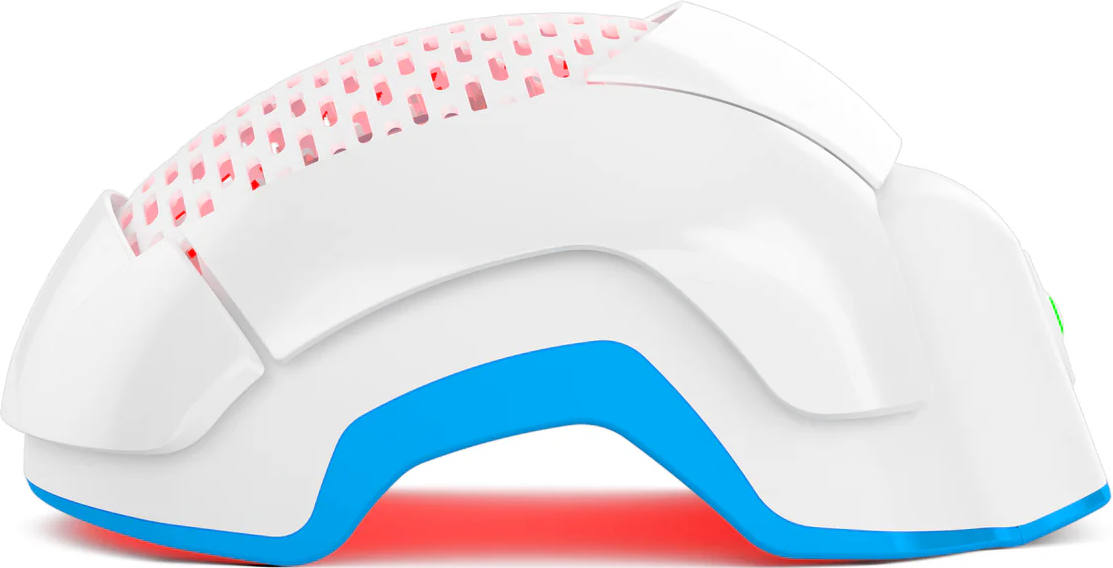

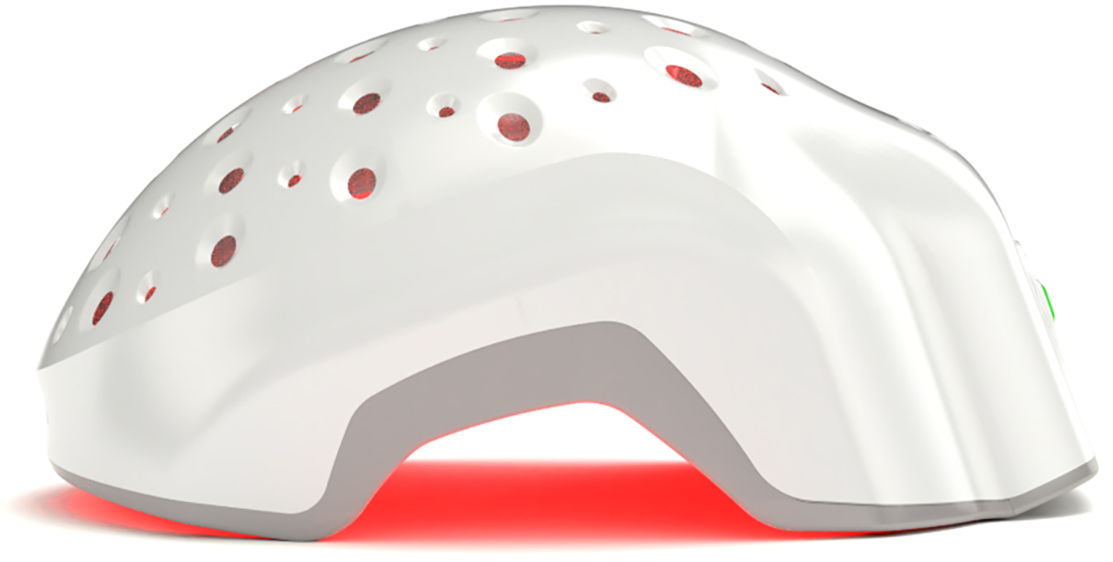

Hair grows from follicles. Not oils. Not brushing. Not irritation.

Coating the strand can improve appearance and reduce breakage. It cannot change hair growth cycles or follicle signaling.

That distinction did not exist in the 1800s. It does now.

And it changes everything.

Why Historical Hair Remedies Still Appeal Today

People like tangible action. Rubbing. Applying. Doing.

It feels reassuring, especially when hair feels out of control.

History repeats when biology gets ignored.

Conclusion

Hair care in the 1800s was creative, resourceful, and often misguided. People worked with the tools and knowledge they had. Oils coated. Brushes cleaned. Chemicals stripped. Tonics promised.

What was missing was follicle biology.

Today, we know better. Hair growth depends on cellular signaling, growth cycles, and safe stimulation at the scalp. Appearance and health are not the same thing.

Understanding where we came from sharpens how we choose now. Less guessing. Fewer illusions. More respect for how hair actually works.

And that shift. Quiet as it is. Matters.